Always Looking:

Religion On The Frontier

Many motives brought people to the New World from Europe. Lust for land; greed for gold and silver and gemstones and furs; hunger for new fisheries after all the herring were fished out of the North Sea; zeal for new converts to Christianity. But one of the motives we love to hear about was the yearning for a land where one could follow one’s own faith without persecution, a yearning that famously brought the Pilgrims to New England, the Quakers and Huguenots and Moravians to Pennsylvania, Catholics to Maryland, Mormons to Utah, Mennonites to Kansas.

Much of early American history includes religion as part of the tale. Often one of the first buildings to be built in a frontier community was a church, sometimes – where population was light and beliefs diverse – a nondenominational church. While churches in American settlements were rarely the center of the community (that typically was the schoolhouse, at least in the Midwest), they were very important. And knowing something about the varieties of faith on the frontier can help explain migration patterns, community organization, and sometimes even how the land was settled up and divided.

In my own family, though much of the information has been lost, it’s known that some on both my mother’s and father’s sides came here from England to join the William Penn community of Quakers in Pennsylvania. The Boones came from Devon to the Oley Valley near Reading; the Reeves family from Essex via Burlington County, New Jersey, to the Chester County area west of Philadelphia.

|

While my kin eventually left the Quaker Church (or were “disowned” for improper behavior such as marrying non- Quakers), family tradition has it that our Quaker heritage shaped some of our personality, which trends toward the mild and peacemaking (in most, though not all, members of the family). And many of my family branches dispersed west across the new land along the general path followed by Quaker settlement – Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa.

Then there were the Piggott, Patterson, and Rogers families: settlers in Missouri before it was part of the United States. (It was Spanish, then, briefly, French.) They brought with them their new Methodist and Baptist faiths and helped found the oldest Protestant cemetery west of the Mississippi still in use, the Cold Water Cemetery

| Cold Water Cemetery near Florissant Missouri |  |

near present-day Florissant, Missouri, which was originally associated with a small Methodist church erected in 1808 that was later converted into a Baptist church. Numerous of my people are interred there. My maternal grandmother was born near there. In fact, my mother’s family to this day are almost all Methodists, with an occasional dalliance with the Baptists.

|

In Iowa, the Blairs and Linvilles of my father’s family helped found the first church of any denomination in Mills County (east of Omaha) in 1853. The Wahbonsie Church (Disciples of Christ) is still standing, in a later construction, though now used only occasionally.

| Wahbonsie Church, Mills County, Iowa |  |

Great-great Grandpa Thompson Milton Blair and his wife Sarah Linville Blair both signed the original Articles of Organization. Many in their rural frontier community were members. And my great-great-great grandfather Zachariah Linville, Sarah’s father, died while trying to bring religion to the gold miners of early California, where he is buried on a hillside near the former Hangtown (now Placerville). Part of family lore, and true. My paternal aunts and uncles in western Oklahoma mostly centered their Sundays, marriages and burials, around the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) near the center of Camargo, which is located on a terrace of arable land above the South Canadian River. It’s the only church I can remember ever noticing in Camargo (though I understand there are a couple of others).

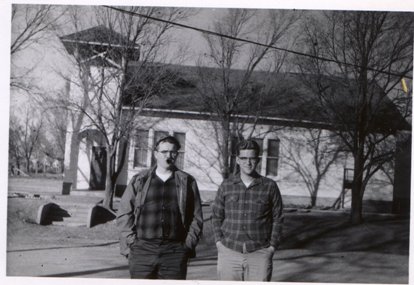

| Charlie and John Blair in the 1950s in front of the Camargo, Oklahoma, Christian Church |  |

| Holy Family parish church Brooklyn, New York |

| Bethany Swedish Lutheran Church Lindsborg, Kansas |  |

Students of genealogy know that church records can be one of the most valuable resources for documenting births, baptisms, marriages, and deaths. Especially the Mormons, Quakers, Catholics and Anglican/ Episcopalian churches keep careful records and often will share them with outsiders, if asked politely. I got much aid in tracing some of my Quaker roots from a friendly researcher at Earlham College (Quaker) in Indiana. Thousands of family history buffs seek assistance from Mormon records. And the parish registers of England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland (and other countries, wherever the records have survived centuries of wars and civil disruption) are essential documents for anyone tracing their earliest antecedents.

|

Religion is still a major part of our lives for most; and in the past it was often, literally, the center of life, the hub of history. Knowing about your family’s religious traditions can be a valuable guide to understanding who you are, and where you came from. Pretty obvious, yes; but worth repeating.

©2010 John I. Blair

No comments:

Post a Comment