Pierre “Le Jardiniere” Cresson

7th Great-Grandfather – Chapter 2

Pierre Cresson was a French Huguenot, who escaped persecution in France at the time of the Reformation by relocating to the Netherlands before making the long voyage to the New World – known then as New Netherland and now called New York. His story encompasses the intrigue of religious persecution and the impact that had on the lives of many brilliant and talented Protestant French citizens. This chapter takes up his life at the time he determined to migrate to the New World – New Amsterdam.

Chapter 1 in the annals of the life of Pierre “The Gardener” Cresson covered his early life beginning in France and the geographical relocation of his family first to Sluis, Flanders and then, along with other refugees from Flanders, to Leyden, Holland. Another family historian has discovered some records that substantiate vital records for our Pierre Cresson. These are mostly original records in the native French as they appear in the archives of Family Search (an arm of the LDS church and a sister site to Ancestry.com). The following is a transcribed document of the recordation of the marriage of Pierre Cresson and Rachel Clausse which also documents the parental identities for both parties:

France, Protestant Church Records, 1536-1897

Name: Pierre Cresson

Event Type: Marriage

Event Date: 05 Jun 1639

Event Place: Sedan, Ardennes, France

Gender: Male

Father's Name: Pierre

Mother's Name: Elisabet Vuilesme

Spouse's Name: Rachel Clausse

Spouse's Gender: Female

Spouse's Father's Name: Pierre

Spouse's Mother's Name: Jeanne Famelart

(Your author shall not introduce all the vital records in this text but will provide a line of descent for reference purposes to guide other family researchers. The additional vital records discovered through Family Search will be added to our tree in Ancestry.com which tree is, by my choice, a public resource. They include birth and baptismal, and death records for children of the couple.)

It is interesting to note this other family historian (Daniel Troublefield) shares in his profile that he speaks both French and English, a fact highlighted by his research into original French documents. The document shared above includes in the original French that Pierre listed his occupation as “serger”, which fact Troublefield reflects:

“Found our Pierre Cresson the younger was a "serger" (silk/linen cloth maker) and "cordonnier" (shoemaker) in the cloth-making industry at Sedan.”The occupation of cordonnier is discovered in the baptismal record for Jacques, a son of the couple, noted 12 March 1640 at Sedan, Ardennes, France. This shows the family still ensconced in Sedan as late as 1640, although that same year he is recorded as being “among the refugees at Leyden.” Perhaps they awaited the birth and baptismal for this child before making that move. [SOURCE:https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DR5Q-3PM?i=53&cc=1582585]

This find prompted my own research into the probable impetus that brought about Pierre’s migratory decision – the move from Sluis, Flanders to Leyden (spelled Leiden today).

“In the 17th century, Leiden prospered, in part because of the impetus to the textile industry by refugees from Flanders. While the city had lost about a third of its 15,000 citizens during the siege of 1574, it quickly recovered to 45,000 inhabitants in 1622, and may have come near to 70,000 circa 1670. During the Dutch Golden Era, Leiden was the second largest city of Holland, after Amsterdam.”[SOURCE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leiden]

This citation also marks the fact that the city sided with the Dutch against the Spanish in 1572, and the citizens’ successful defense of the Dutch army endeared them to William I of Orange, so much so he rewarded the citizenry for breaking the siege by establishing the University of Leiden in 1575. Considering Pierre’s early grounding in the Huguenot’s Reformist beliefs, it is yet another strong indication this played a large role in his decision to move his family to Leyden.

By tracing other vital records, we can follow the family’s movement. For instance, on 31 Jan 1644, the baptism of son Estienne is recorded at Delft, South Holland, The Netherlands. This baptism is witnessed by Estienne Trouillard and by Elisabet Willesme (mother of Rachel Clausse whose name is spelled Closse in this document).

At some point, it appears our Pierre changed not only his locale, but his occupation from that of textile artisan (linen clothmaker) and shoemaker to gardener, par excellence. Historical records in America record Pierre’s skill as being so remarkable that Governor Stuyvesant sought him out upon his arrival in 1657 and proffered an arrangement whereby Pierre could satisfy the debt owed New Amsterdam for portage for his entire family from Amsterdam to the New World. The offer was accepted, and the following year Pierre embarked on a return trip to Holland to employ other agriculturalists: landscaping and gardening artisans. The trip back to New Amsterdam is documented. On 25th April 1659, Cresson and his artisans set sail aboard De Bever (The Beaver) from Amsterdam and arrived some six weeks later in the Manhattans.

Now for you knowledgeable historians, Governor Peter Stuyvesant was quite a character. He was born in 1592 in The Netherlands to a Dutch Reformed Calvinist minister and his wife. He was expelled from his university for having seduced the daughter of his landlord. While in the university, however, he had excelled in his studies, majoring in languages and philosophy. He soon joined the Dutch West India Company and enjoyed numerous postings with that company, serving in positions of ever-increasing authority. By the ripe young age of 30, Stuyvesant was assigned as acting governor of the colonies of Curacao (the main Dutch naval base in that colony) as well as for Aruba and Bonnaire. He served in those positions from 1638 until 1644. As reported in Wikipedia:

“In April 1644, he coordinated and led an attack on the island of Saint Martin – which the Spanish had taken from the Dutch, and had almost been recaptured by them in 1625 – with an armada of 12 ships carrying more than a thousand men. He invested the island (*) when the Spanish would not surrender, but was not successful in preventing them from getting supplies from Puerto Rico. A cannonball crushed Stuyvesant's right leg, and it was amputated just below the knee. Still in severe pain, he called off the siege a month later.(*) Laid siege to

Stuyvesant returned to the Netherlands for convalescence, where his right leg was replaced with a wooden peg. Stuyvesant was given the nicknames "Peg Leg Pete" and "Old Silver Nails" because he used a wooden stick studded with silver nails as a prosthesis. The West India Company saw the loss of Stuyvesant's leg as a "Roman" sacrifice, while Stuyvesant himself saw the fact that he did not die from his injury as a sign that God was saving him to do great things. A year later, in May 1645, he was selected by the Company to replace Willem Kieft as Director-General of the New Netherland colony, including New Amsterdam, the site of present-day New York City.”

The appointment as Director-General of the New Netherland colony took time to be affirmed. He and his new bride finally arrived in the New World in May of 1647. The once thriving colony had suffered badly from the poor management of Kieft, whose travails were certainly worsened by his descent into alcoholism. Few of the original male colonists remained, the villages had been left to deteriorate, and confidence of the colonists was badly shaken. Stuyvesant saw this challenge as the “great” work for which God had saved his life and felt duty-bound to do his utmost to improve the lot of those colonists who remained. He is reported to have vowed,

“I shall govern you as a father his children.”

The young colony was not well protected and was beset by a number of adversaries. The English who had colonized the land just north of New Amsterdam claimed or chose to assert claims of ownership of the land. Native Americans also posed a threat to the young colony. In addition, the Dutch West India Company had stretched itself thin in its eagerness to extend its reach.

“In 1657, the directors of the Dutch West India Company wrote to Stuyvesant to tell him that they were not going to be able to send him all the tradesmen that he requested and that he would have to purchase slaves in addition to the tradesmen he would receive.”Thus, Stuyvesant’s decision to make that most acceptable proffer for Pierre Cresson to enlist artisans from The Netherlands to come to join their colony in exchange for payment in full of the steerage cost for Pierre Cresson and his family to New Amsterdam.

Gov. Stuyvesant, if judged on his vow to be a father to the colonists, was a stern and dictatorial father. Having been born to a Dutch Reformed Calvinist minister and having enjoyed the freedom in the New World to worship as he pleased, it was not his wont to extend that freedom to others in pursuit of religious freedom. He was particularly prejudicial in his treatment of Jewish immigrants, but he was equally disdainful of Quakers – in fact, of almost any who sought to worship under any doctrine but that of Stuyvesant’s own religious choice. When pressed to share power and decision making with other worthy colonists, he absolutely refused. Further, he was adamant in his attempt to quell alcoholism, to the extent of barring certain commercial efforts and even publicly shaming anyone thought to be over-indulging. These stern disciplinarian actions did not endear Stuyvesant to the populace. This would come to bear bitter fruit when, in 1664, the British invaded and the populace refused to assist Stuyvesant in defense of the colony. He was forced to turn it over to the English, thus bringing shame upon himself by his long-time employer, the Dutch West India Company. He was recalled, denounced, and after his thorough dressing down chose to return to his home in the Bowery where he would remain until his death in 1672.

Our Pierre returned on his second trip to New Amsterdam in April of 1659 and immediately dedicated himself to the betterment and protection of his new home. By 16 August 1660, he was appointed commissary (or Judge) to New Haarlem. He joined in the defense of the young colony and is noted as having served as corporal of 1st Company in 1663 in the expedition against the Indians at Esopus.

1663: Astounding news reached the villagers of an Indian onslaught and massacre at Esopus on June 7th in which some of their friends and kinsfolk were sufferers… Van Imbroch and her little Lysbet were in captivity with the savages. Harlem was all alarm. The town people assembled June 12th, by orders from below, and with the advice of the magistrates, Montagne, Claessen, Tourneur, and Muyden, and clearheaded Slot, asked to sit with them as extraordinary schepen, proceeded to take the necessary steps for inclosing the village with a line of stockades, and putting it in a complete state of defense. Ten persons were designated to cut palisades and four others to draw them to the village; while Tourneur and Jaques Cresson were deputed to procure a supply of arms and ammunition promised from the Manhattans. At the same time the dozen or more soldiers stationed here, together with the settlers (exclusive of the presiding magistrates), forty persons in all, were formed into military companies, which, after some time spent in changing and rearranging the ranks were duly organized. For officers the eldest and most capable persons were selected. In the first company, Pierre Cresson, in the ripe manhood of fifty-odd years and still very active, was assigned the chief and responsible command of corporal…: Immediately following the massacre at Esopus, forty persons at New Harlem were formed into militia companies. Daniel TORNEUR, Jan La MONTAGNE, Michiel MUYDEN, Jaques CRESSON and Jan P. SLOT, were supplied with firelocks; and Isaac VERMEILLE, Abram VERMEILLE, Pierre CRESSON, Jean Le ROY, Glaude Le MAISTRE and Aert P. BUYS, with musquets. Also listed as privates were Joost Van OBLINUS, Jan SCHOENMAKER, et.al. [James Riker, REVISED HISTORY OF HARLEM (1904), p.201-203.” The savages at Esopus were soon made to flee before the advance of the resolute Dutch soldiers, but armed parties still kept the warpath threatening vengeance on the whites and whoever should aid them.”

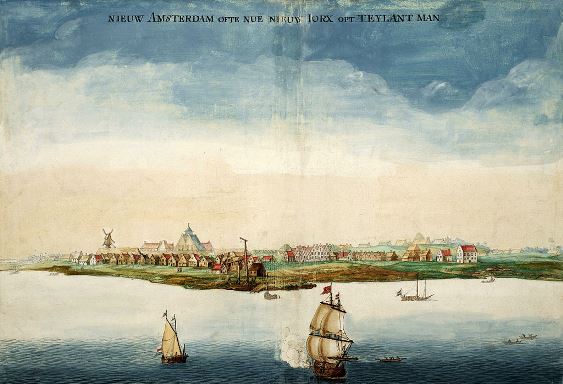

But his work as a landscaper and agriculturalist is what has placed his name in the history of Harlem. He settled near Gov. Stuyvesant in the farm area on the lush plot of land near the river. A painting of New Amsterdam as it appeared in 1664 is shown here, entitled “Geheugen van Nederland” or Memory of The Netherlands, by Johannes Vingboons.

His land in New York was where the Bowery is today. Pierre Cresson raised many beautiful flowers in his yard - to such an extent that his neighbors emulated his example and the street became known as the "Bower" ... so it was because of Pierre that the Bowery was so named.

|

The farmlands were known as The Bowery and, at that time and for many, many years afterward, were the epitome of grand and glorious flowering trees and well landscaped lawns and gardens. It was only after the lands were broken up and the original inhabitants died off or removed their families that the Bowery became associated with ruin and despair.

Another entry in the Revised History of Harlem (City of New York): Its Origin and Early Annals, by James Riker and Henry Pennington Toler refers to Pierre’s time as a complainant rather than as a Judge, the year 1670 (NOTE: gl translates to guilders):

On the same date the 19th the court room witnessed an unusual scene. Pierre Cresson, three years before, had leased his farm to Glaude Delamater and things had not gone smoothly between them. In a sharp dispute about one of the oxen which, as appeared, had died through Delamater's neglect, the latter called Cresson a villain for driving away his wife. Mrs. Cresson was spending a season at Esopus. Coming into court with his complaint where Delamater was sitting as one of the magistrates, the usually amiable and prudent Pierre, overcome by anger told Glaude that he ought to slap his face. Delamater pretended forgetfulness but remembered that plaintiff had called him names, too. The court regarding both parties at fault fined each 12 gl and costs. Unhappily this did not end the quarrel between the Walloon and Picard…

The ill feeling between Cresson and Delamater again showed itself when the term of three years, during which the latter had worked Cresson's farm, was closing. The court had ordered payment for the lost ox, but one of the farm tools was found broken. On September 1st Pierre in open court demanded his tools of Delamater, who was seated on the bench with his brother magistrates. Glaude answered that the broken tool was at the smith's, being mended. The court, hearing what passed between the parties, referred them to their agreement of September 5th, 1667, but put the court charges upon Cresson. Shortly after Glaude sent Pierre word by the constable to come and examine his tools. Cresson would do no such thing, but again went to the court room, October 6th, and repeated his demand for the tools. Delamater now promised to send them by his son; but the court, to vindicate its injured dignity, directed Pierre to fetch the tools himself from the defendant's house and fined him 12 gl and costs of suit. Vexed at what he conceived to be a harsh judgment, Cresson at the sitting of the court December 1st, entered, and asked if he must satisfy the sentence given against him. He was answered, “Yes.” Now passion got the better of him, and he denounced the magistrates as “unjust judges,” adding, with other abusive words, that “instead of judges they were devils!” On this the court ordered the constable to take Cresson into custody and convey him a prisoner to the High Sheriff at New York, to be duly proceeded against. Cresson was soon released, but, now bent upon leaving the town, had his wife at Esopus apply for a building lot in that village, and this she asked for and obtained April 15th, 1671.

We find a delightful entry in the Revised History of Harlem describing village life in that village in 1673:

“This chapter of incidents may fitly close with a glance at the village of New Harlem as it was in the autumn of 1673. How quaint an aspect has the Dutch settlement as e’en now its plain wooden tenements, embowered in foliage whose variegated hues already tell the declining year, rise modestly to view. Their humble eaves, keeping line with the street, lift themselves but one low story, yet the extraordinary slope of the thatched roof gives space to the loft above, so useful for many domestic purposes. Aside the house, quite too near for entire safety, stands the ample and well-stored “schuer” or barn, in its squatty eaves and lofty ridge the very counterpart of the dwelling, but by a noticeable contrast turning its gable with huge gaping doors to the highway. In the spaces between buildings and homesteads flourish rows of choice imported fruit trees, apple, pear, peach, cherry, and quince, and the no less prized garden and ornamental shrubs, the Dutch currant, gooseberry, and evergreen box, dwarf, and arborescent. Tidiness reigns, at least about the dwelling and within reach of the busy housewife's mop and broom but all betokens a plainness and frugality in wide contrast with the elegance of modern living. The daily life of the villagers, -- but let us first note the occupants of the principal dwellings ere we cross the threshold to explore the humble sphere of their domestic economy. Here at the river end, where, about the tavern, smith-shop, church, and ferry gather the stir and business activity of the village, is the comfortable home of the French refugee and newly appointed schepen, David Demarest…This last looks out to the south upon the square or green about the landing place. Demarest's neighbor over the cross street is Glaude Delamater, recent magistrate, testy but kind hearted, his double erf joining that of Cornelius Jansen, late constable, a young but rising man in the town and at whose friendly inn, -- where swinging signboard and feeding troughs mark it merely as the village hostel, but to Kortright, Bogert, and others the veritable counterpart of Mynheer's inn at Schoonrewoer, -- the passing traveler stops for refreshment or the wiseacres of the dorp resort to swallow the latest bit of news or scandal in a bumper of Kortright's beer. Opposite the tavern, past the second crossway, lives the Picard, good Pierre Cresson, from his occupation called by his Dutch neighbors ‘de tuynier’ or the gardener whose erf joins at its rear, or north side, to that of Daniel Tourneur, but just deceased, and westerly to that late of Hendrick Karstens but now of the worthy Joost Van Oblinus, schepen…”

In a later entry, we find note of Pierre in 1677:

“This year another French refugee left the town with his family. This was Pierre Cresson. After selling out his farm May 23, 1677, to Jan Hendricks Van Brevoort, who had had it a year under lease, he built upon and occupied his outside garden No 14. This he now sold March 5, 1679, to Jan Nagel who owned No 13 for 100 guilders, in goods or grain, a pair of oxen, one cow, and a half-firkin of soap. Cresson removed to Staten Island, having already secured a lot of land at or near Long Neck, on the northwest side of the island for laying out, which an order had issued from the Secretary's office May 14, 1678. A small stream, on which lay his meadow at Sherman's Creek, was long called after him Pieter Tuynier's Run.”(NOTE: Pierre Cresson was also referred to as Pieter and ‘de tuynier’ translated as ‘the gardener’.)

In 1679 he sold his lands in Harlem and moved to Staten Island where he obtained a lot at or near Long Neck by the Fresh Kill on the northwest side of the island.

Riker and Pennington explore the character and origins of those founding families of Harlem, New Amsterdam:

“Very interesting is Picardy, whence came so many of the French exiles who made their homes at Harlem for longer or shorter periods; in all some thirty families of which a full third were Picards or of Picard descent. Of this class were our Tourneur, Cresson, Demarest, Casier, and Disosway, all of whom, except the last, served as magistrates. But who were the Picards? A quite superior people to the average French; being of mixed origin, descendants of both Belgae and Celtae, and occupying the border between these two ancient nations, or rather the district which parted the Celtae from the Nervii, the most invincible of the Belgic tribes. Thus, sanguine and choleric like the Celts, they approached the Belgae in their moral and physical stamina. In stature above the medium, with usually a well-developed frame, they betrayed their affinity to the Walloons, whose patois, rough and disagreeable, theirs resembled; yet, proud and spirited, they held those neighbors and all others in secret disdain. The love of independence was not so strong within them as the love of equality; it was here their vanity showed itself, but it tempered the popular homage to wealth or titles. Though hasty, blunt, and obstinate, yet without the effrontery of the Normans or the superstition of the Champenois,-- and more religious than either,-- the Picards were withal lively, generous, honest and discreet. Their conversation sparkled with wit, mirth, and sarcasm. Necessity, rather than inclination, made them industrious, yet, they yielded their full share of workers and proficients in the arts and sciences; as also of able physicians and divines,-- some of the latter as much distinguished in the controversial history of the Reformation as others had been who were its earliest champions. With intelligence, and a manly aim to excel in what they undertook, even though it were but agriculture,-- in which by far the greater number were engaged,-- the Picards could not but add a valuable element to any society so fortunate as to attract them.”

Later, in the book is made reference to our line of descent:

“The old schepen Jan Slot ended his widowerhood by choosing another wife and provident Pierre Cresson, whose son Jaques had married since coming to Harlem, found a worthy companion for his daughter, Christina, in a young man from St. Lo in Normandy named Letelier, now a magistrate at Bushwick. Jean Letelier was one of the fourteen Frenchmen by whom Bushwick was settled in 1660, and was one of its first schepens, March 25, 1661. He always signed his name simply Letelier, the usual mode among the French gentry. In 1662, he gave three guilders toward the ransom of Teunis Cray's son Jacob in captivity with the Turks. Removing to New Utrecht, he there died September 4, 1671. In his will, (to which Abraham du Toiet is a witness) he speaks of his children, but does not name them. His widow married Jacob Gerrits De Haes, by whom she had issue, Jacob, born 1678; John, born 1680; etc. Letelier was usually called by the Dutch Tilje (Tilya) and whence perhaps the family of Tillou or Tilyou, whose ancestor, Pierre (see NY Gen. and Biog. Rec., 1876, p. 144), if the son of Jean, took the name of his godfather Cresson.”

A personal insight – a treasure to a genealogist! – is found as a footnote to the Revised History of Harlem (stet), along with other entries pertaining to Pierre Cresson:

Pierre Cresson or Moy Pier Cresson (me, Pier Cresson) as he always wrote his name, is the subject of interesting notice in the journal of these Labadists date of October 13, 1679, they say: “We pursued our journey this morning, from plantation to plantation, the same as yesterday, until we came to that of Pierre le Gardinier, who had been a gardener of the Prince of Orange, and had known him well. He had a large family of children and grand children. He was about seventy years of age, and was still as fresh and active as a young person. He was so glad to see strangers who conversed with him in the French language about the good, he leaped for joy. After we had breakfasted here they told us that we had another large creek to pass called the Fresh Kill, and there we could perhaps be set across the Kill van Kol to the point of Mill Creek, where we might wait for a boat to convey us to the Manhattans. The road was long and difficult, and we asked for a guide, but he had no one, in consequence of several of his children being sick. At last he determined to go himself and accordingly carried us in his canoe over to the point Mill Creek in New Jersey.”

Here they “thanked and parted with Pierre le Gardinier.”

Pierre and his son Joshua had each obtained a grant of 88 acres on the west of the island which were surveyed for them December 24, 1680 and patents issued December 30. This is the latest notice found of Pierre. His children, so far as appears, were Susannah, Jaques, Christina, Rachel, Joshua, and Elias. Susannah, born at Ryswyk, married, 1658, at New Amsterdam, Nicholas Delaplaine. Her father gave her a marriage portion of 200 guilders. Christina, born at Sluis, married Jean LeTelier and Jacob Gerritsz Haas. Rachel, born at Delft, married David Demarest, Jr., Jean Durie, and Roelof Vanderlinde. Joshua Cresson, born 1659, and Elias, born 1662, both lived upon Staten Island, the latter, we presume, succeeding to his father's farm. He was high sheriff of Richmond County, under Leisler. One Joshua Cresson lived at North Branch NJ in 1720.

Jacques Cresson of good repute and much respected at Harlem where he owned property and held office, married, 1663, Marie Kenard of whom we have given some account. They had issue, Jaques, born 1665; Maria, 1670; Susannah, 1671; Solomon, 1674; Abraham and Isaac, 1676; Sarah, 1678; Anna, 1679; Rachel, 1682. Jaques’ injury, January 31, 1677, and sad death August 1, 1684, we leave unrecorded. His widow, with her son Jaques or Jacobus, sold their house in Stone Street September 9, 1685, and taking a church letter, November 25, she sailed with her family for the Island of Curacao. Later they returned, and Mrs Cresson reunited with the church at New York May 28, 1701, but it is evident they soon left again for Philadelphia. Solomon Cresson served as constable there in 1705 and others of the family are found in that vicinity. The descendants include the late eminent philanthropist Elliot Cresson and the present Dr Charles M Cresson. The name of late years has worked up the valley of the Susquehanna into New York State.”

The Labadists who were quoted above were a religious group who toured the area with hopes of increasing their number by befriending the populace while proselityzing. Some embraced the Labadist views including Jaques Cresson; however, Cresson could hardly have joined the community as he died but a year after Peter Sluyter's second arrival at New York July 27 1683, on his way to Maryland. Nowhere is it noted Pierre waivered from his firm Protestant reformist beliefs.

Finally, we find where Pierre and Rachel made their Wills:

“Pierre Cresson and Rachel Cloos, his wife, “both being sound of body,” made their joint will March 15, 1673. Cornelis Jansen and Jan Nagel, witnesses. How sensible and wise, thus in health, to calmly weigh the fact of their mortality and deliberately set their house in order. Leaving fifty guilders to “the church at New York,” they say, “whereas their daughter Susannah has enjoyed as a marriage portion the value of two hundred guilders, so the testators will that at the decease of the longest liver each of their other children then living shall draw the like 200 guilders, and our youngest son, Elie, if he is under the age of sixteen years, also a new suit of clothes becoming to his person from head to foot.”

Pierre’s death occurred 13 October 1681, in what is now known as Brooklyn, Kings County, New York. His place of burial is not known. Rachel survived until about 1692 and is believed to be buried beside her husband, although that place of burial is not known.

The line of descent from Pierre, the Gardener to William, Prince of Orange, to your author is as follows:

-

Pierre "Le Jardiniere" (Pieter) Cresson (Croisson) 1609-1679, my 7th great-grandfather was the father of:

- Christina Cresson (Garrison) 1641-1708, my 6th Great-Grandmother, was the Daughter of Pierre "Le Jardiniere" (Pieter) Cresson (Croisson) and the mother of:

- Jacob Garrison (Gerritszen De Haes) Jr. 1676-1751, my 5th Great-Grandfather, was the Son of Christina Cresson (Garrison) and the father of:

- Christiana Garrison 1702-1757, my 4th Great-Grandmother, was the Daughter of Jacob Garrison (Gerritszen De Haes) Jr. and the mother of:

- William "P.R." Joslin 1757-1846, my 3rd Great-Grandfather, was the Son of Christiana Garrison and the father of:

- William (James) Riley Joslin 1792-1871, my 2nd Great-Grandfather, was the Son of William "P.R." Joslin and the father of:

- William Henry Joslin 1837-1921, my Great-Grandfather was the Son of William (James) Riley Joslin and the father of:

- James Arthur Joslin 1874-1956, my Grandfather, was the Son of William Henry Joslin and the father of:

- Lena May (Mae) Joslin (Carroll) 1918-2010, my mother, was the Daughter of James Arthur Joslin.

No comments:

Post a Comment